Part 1, which appeared in the May 2005 issue, detailed NABI’s decision to embrace a bold new strategy for transit bus design and engineering. The Federal Transit Administration (FTA) helped NABI bring the bus to reality in the U.S. market by granting a two-year Buy America waiver. From there, unforeseen manufacturing problems compounded by the slide of the U.S. dollar in Europe began to turn the CompoBus dream into a nightmare…

In July 2001, even before the FTA waivers were under consideration, NABI broke ground for a new facility in Kaposvar, Hungary, southwest of Budapest. The facility would be purpose-built for composite bus fabrication and final assembly.

In January 2002, the company secured another 30-unit CompoBus order from the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority. It later exercised an option for another 70 buses, becoming the largest CompoBus customer. Deliveries of these buses are being completed later this year.

NABI accelerated its development of the Kaposvar facility after the FTA waivers were announced. At a cost of more than $4 million, the first phase of the new factory was opened in June 2002 and began turning out CompoBus body-chassis shells later that year. A second, $6 million phase of the final-assembly facility was finished in 2003.

With both the investment in the factory and the product development program, the company risked more than $30 million in 2005 dollars.

Manufacturing costs, delays

From the outset, the program was plagued by a series of unforeseen costs and delays. Many of these challenges were not unusual for transit bus manufacturing, but some were.

First and foremost, recruiting and training skilled workers in a smaller city such as Kaposvar, whose economic base is primarily agricultural, proved to be a difficult challenge. It would have been difficult enough to find and train workers for steel bus production, but compounding the difficulty was developing the workforce for advanced composite fabrication.

In addition, because of the decision to do almost everything at the new facility, a supply chain had to be developed almost from scratch. Other NABI buses only begin production in Hungary, with more than 60% of the component value sourced in the U.S. for compliance with Buy America regulations. Wiring harnesses, hydraulic and pneumatic systems, major components — all had to be shipped from the U.S. only to be put in a bus that was bound back for the states, or local suppliers were found. These logistics alone consumed months of planning.

Other delays were even more fundamental. One disadvantage of advanced composites and even conventional fiberglass lay-up is that they are time-consuming processes. No matter how much NABI engineers tried to squeeze out of the material requirements or streamline production, they could not make much of a difference. One internal estimate found that comparing the production of CompoBuses with that of steel buses, all else being equal, CompoBuses took nearly 50% longer to make.

In addition, the weight of the vehicle began climbing, partly to engineer in requirements of the early customers, such as anti-graffiti stainless steel seating and interior panels. Moreover, the components remained as heavy-duty as on steel buses, mainly to ensure fleet commonality desired by most transit agencies. The result was that the CompoBus was only about 2,000 pounds lighter than NABI’s 40-foot low-floor steel model, vastly less than the original target.

Final efforts and decisions

The manufacturing costs were not envisioned and thus not figured into NABI’s pricing with the early CompoBus customers. Compounding this problem, the Hungarian forint, which is tied to the Euro, appreciated rapidly against the U.S. dollar during the past four years. In the past two years alone, the dollar lost more than 20% of its value, making any goods imported from Europe at least that much more expensive than before. However, because prices were set at time of contract award, what was once profitable became a big money-loser.

To reflect true costs, NABI management began raising CompoBus prices by as much as 30% over what it quoted to early customers and prospects. The decision destroyed the economic rationale for the 40-foot “shoebox” CompoBus design, because its business case was purely based on weight-related fuel and other operational savings. For the 45-footer, the only documented productivity gain was its 15% additional capacity, which could not justify a 30% premium. The only other asserted advantages, passenger-luring design and crashworthiness, simply could not be supported by real-world data that did not yet exist. Thus, no new orders were received after the end of 2002.

FTA won’t extend waiver

The final coup de grace came when the FTA denied NABI’s extension of its waivers this past December. The original waivers had expired in March 2004, which meant that for any new business won from solicitations or contracts after that date the buses had to be made compliant with Buy America rules.

In seeking an extension of the waiver, NABI argued that it was financially unable to transfer manufacture of the CompoBus component from its facility in Hungary to its plant in the U.S. To do so would have driven the cost of production, and therefore the price, even higher. However, the FTA replied that this was a business decision, not a technical one, and that NABI’s licensing deal with TPI Composites allowed for the manufacturing to take place anywhere NABI chose.

Based on its inability to commercialize the technology at a price that the industry was willing to pay and in a manner compliant with federal law, NABI saw no future for CompoBus. Accordingly, it announced that it would lay off a third of its workforce in Kaposvar and cease production after it completed existing contracts.

Despite the dire predictions of some financial analysts in Europe, the decision affects less than 10% of the company’s production slated for 2005 and even less beyond this year.

Industry implications

The death of CompoBus raises several important questions. After nearly $100 million spent in both the public and private sectors, will lighter-weight buses with advanced materials ever be commercially viable? And if so, will their price tags ever be justified by higher operational productivity?

Can the U.S. industry assume the commercial risks demanded — at least encouraged — by their customers with a supply chain largely derived from American companies and workers?

The recent record is not great on two important points. First, most of the innovations so attractive to U.S. transit agencies of late, whether rail or bus technologies, have been foreign born — often with those countries’ taxpayer contributions. Should the U.S. do the same and, if so, how should it be different? Which raises a second point: With nearly all bus and railcar manufacturers either posting a loss, restructuring or both, they are in no shape to take on highly risky research and development without some assurances from the market, beyond lip service.

Advanced technology does not solely pursue ridership or commercial goals. Which is why virtually every policy change in the name of ridership as a performance measure threatens a variety of policies with other objectives, ranging from economic development as a criterion for New Starts to the FTA’s stated push for cleaner vehicles.

For skeptics of the last point, what would the industry do if it discovered that changing the modal split with 1990-standard diesel engine buses did more for cleaner air and reducing global warming than if every bus in the nation’s fleet had hydrogen propulsion, but there were fewer buses than are operating today? The point is that we may have decoupled the true benefits of public transportation usage from its fleet acquisition strategies.

The name CompoBus could be shorthand for another serious question today: What is the true mission of public transportation?

To read part one in the series, click here.

The Death of a Radical Idea, Part 2

Soon after North American Bus Industries poured millions of dollars into development of Hungarian manufacturing facilities for the CompoBus, a series of setbacks began to erode the vehicle's viability. Conclusion of two-part series.

More Management

FTA Invests $100M to Strengthen Transit for 2026 World Cup

The funding will ensure communities can expand transit options to meet increased demand for services around stadiums.

Read More →

ENC Names New VP of Transit Sales

John Obert previously served as regional sales manager for ENC since joining the company in June 2025.

Read More →

New 2026 Plan Aims to Expand Transportation Access Across Virginia

Over the next four years during the Spanberger Administration, DRPT will use the plan to prioritize funding for human service transportation projects and programs that reduce barriers, expand access, and promote equitable mobility, said department officials.

Read More →

Via Launches Mayors Council to Accelerate Transit Innovation Nationwide

A new advisory group of current and former city leaders will collaborate on funding strategies, technology deployment, and best practices to modernize U.S. public transit systems.

Read More →

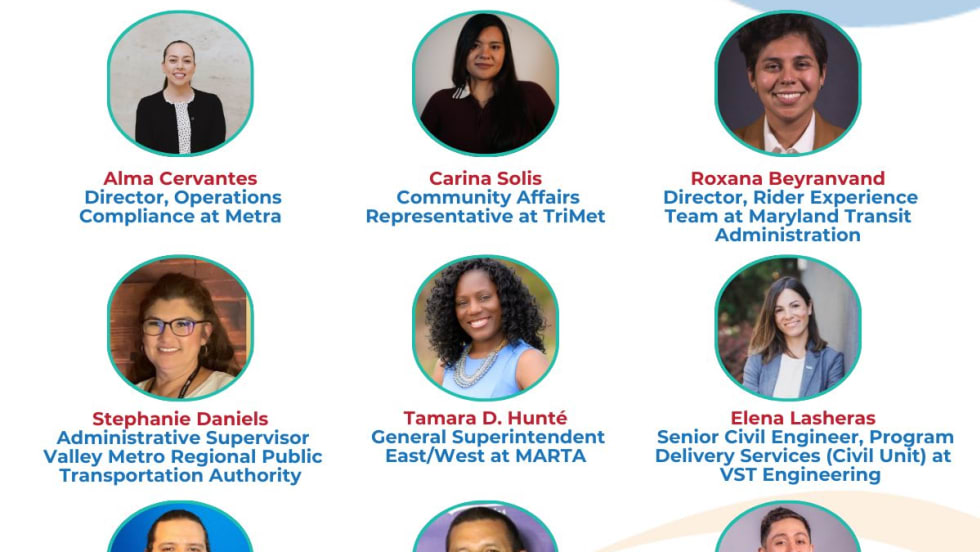

Latinos In Transit Wraps Inaugural Navigate Mentorship Program,

The LIT Navigate Mentorship Program was launched as a structured, low-cost opportunity for active LIT members, focused on intentional growth, workforce development, mentorship, networking, and education.

Read More →

WMATA Expands U-Pass Program

Approved as part of WMATA’s Strategic Transformation Plan, the expanded program introduces new pricing and participation options that make it easier for colleges and universities to join and for more students, such as part-time, community college, and graduate students, to benefit from accessible transportation.

Read More →

People Movement: New CEO's in Georgia, California

In this edition, we cover recent appointments and announcements at Savannah's CAT, California's VVTA, STV, and more, showcasing the individuals helping to shape the future of transportation.

Read More →

How a Family-Run Company Built One of Atlantic Canada’s Most Trusted Transportation Providers

Family-run Newfoundland-based operator earns top honors with unwavering commitment to safety, innovation, and community.

Read More →

Bobit Business Media Expands Fleet Technology Platform with Acquisition of Roadz Partner Portfolio

Bobit Business Media has acquired key partner agreement assets from Roadz, expanding its role as a go-to-market partner for fleet technology providers and strengthening its digital sourcing capabilities.

Read More →

METRO Magazine Announces Return of Annual Buyer’s Guide

The revamped Buyer’s Guide will reach METRO’s audience of more than 17,000 print and digital subscribers, providing suppliers with year-round visibility in front of transit agency leaders, motorcoach operators, and industry decision-makers across North America.

Read More →